Drug-coated balloon (DCB) angioplasty appears to offer similar benefits as plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA), with or without stenting, for patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) who are undergoing endovascular femoropopliteal segment lower extremity revascularization, according to new meta-analysis data presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Society for Vascular Surgery (CSVS) in Ontario, Canada (Sept. 26–27).

Investigators from University of Toronto, led by senior author David Szalay, MD, associate professor in the department of surgery, conducted a meta-analysis that analyzed data from six clinical trials comparing POBA with DCB for the treatment of the femoropopliteal segment in patients with CLTI.

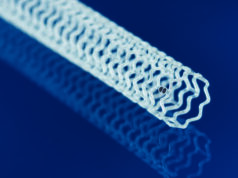

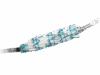

The study looked at four key outcomes: freedom from major amputation, major adverse limb events, the need for additional procedures, and mortality. The goal was to see whether using drug-coated devices, which release the medication paclitaxel, led to better results than using plain balloons. Data was gathered from Embase, MEDLINE, and relevant articles cited in major guidelines on peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Findings showed there was no statistically significant difference in limb events or mortality between DCB or POBA. After synthesizing evidence using the GRADE tool, all key endpoints except mortality were rated with a moderate to high degree of certainty. “The results show there isn’t a statistically significant difference in terms of the four outcomes we analyzed when comparing a drug-coated device to a plain balloon angioplasty,” said first author Allen Li, MD, a second-year integrated vascular surgery resident at the University of Toronto.

Though the absence of a clear difference might appear to narrow the decision-making process, co-author Arshia Javidan, MD, a fifth year integrated vascular surgery resident at the University of Toronto, said the implications are far more nuanced due to the complexity and heterogeneity of the CLTI population. “It will always depend on the specific patient and their anatomy rather than a large paintbrush that we can sweep across the whole field and say we should or shouldn’t use [paclitaxel] in these scenarios,” said Javidan.

Li and Javidan both emphasized that the study’s overall strengths and limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. “One of the biggest limitations of the study, and with every high-level meta-analysis, is that it is not patient-level data,” said Javidan. “These are outcomes taken in aggregate where you lose so much of the granularity that exists in making these decisions.”

The study contributes to ongoing discussions about using drug-coated devices in clinical practice. Javidan said patients with CLTI are high-risk and prone to restenosis, and paclitaxel effectively targets neointimal hyperplasia. While previous research raised concerns about increased mortality with paclitaxel, he said that this has not been consistently supported by later data. “The messaging around paclitaxel-coated devices is that it really is patient dependent,” said Javidan. “You have to choose the right device for the right patient.”

Earlier this year, new data emerged showing drug-coated balloons and stents were not associated with reduced risk of amputation or improved quality of life compared with uncoated devices in the SWEDEPAD 1 and 2 trials. In addition, higher five-year mortality with drug-coated devices in patients with intermittent claudication was noted, leading researchers to stress that the safety of paclitaxel-coated devices is an “ongoing discussion.” These late-breaking findings were presented at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2025 congress in Madrid, Spain, and simultaneously published in The Lancet.

Javidan noted that this ongoing debate is compounded by foundational issues in how research is conducted. “Our ability to synthesize evidence through meta-analysis is fundamentally limited by the heterogeneity in how major trials define their patient population, their endpoints, and even the anatomy of the lesions they are treating,” he said. “Adopting universal classification and anatomic standards, like WIfI and GLASS, and demanding precise definitions for endpoints are not academic exercises — they are essential for delineating clinical truth and improving patient safety.”

Despite this and other challenges, Li and Javidan said the field has made significant progress over the past decade. “We’ve come together and have come up with what is close to global consensus guidelines on a lot of these definitions,” Javidan said.

Li and Javidan also pointed to future directions in CLTI research, including the use of large-scale databases like the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) for patient-level analyses. “What is needed now is really looking specifically in the subgroups of CLTI,” Li said. “PAD exists on a spectrum. We saw from the initial trials looking at DCBs in claudicants there were significant benefits. Similarly, CLTI also has a spectrum — patients can present with rest pain, minor tissue loss, or major tissue loss, and have varying anatomic and patterns of arterial disease. Looking in specific subgroups and seeing whether or not one subgroup might benefit more, that’s the next step in applying the results of this study.”